In a fully circular economy, nothing becomes waste. That includes all the components and materials inside smartphones, laptops, and other electronic devices.

Our global economy is far from circular.

Recycling rates for electronic waste (e-waste) are estimated at 17% globally. Most of the recycling happens in Europe, where the rate is approaching 50%. The Waste from Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) directive, which went into effect in 2012, is largely responsible.

In the Americas, e-waste recycling rates are very low. Although it has been nearly 20 years since California enacted the first e-waste regulation in the US, only half of the states in this country have followed in California’s footsteps.

While government regulations at the local, state, and national level can help improve e-waste recycling rates, the businesses that make electronics must be part of the solution.

This blog post will highlight progress and suggest further actions by covering:

- Urban mining

- Right to repair

- Opportunities in the semiconductor supply chain

Urban Mining

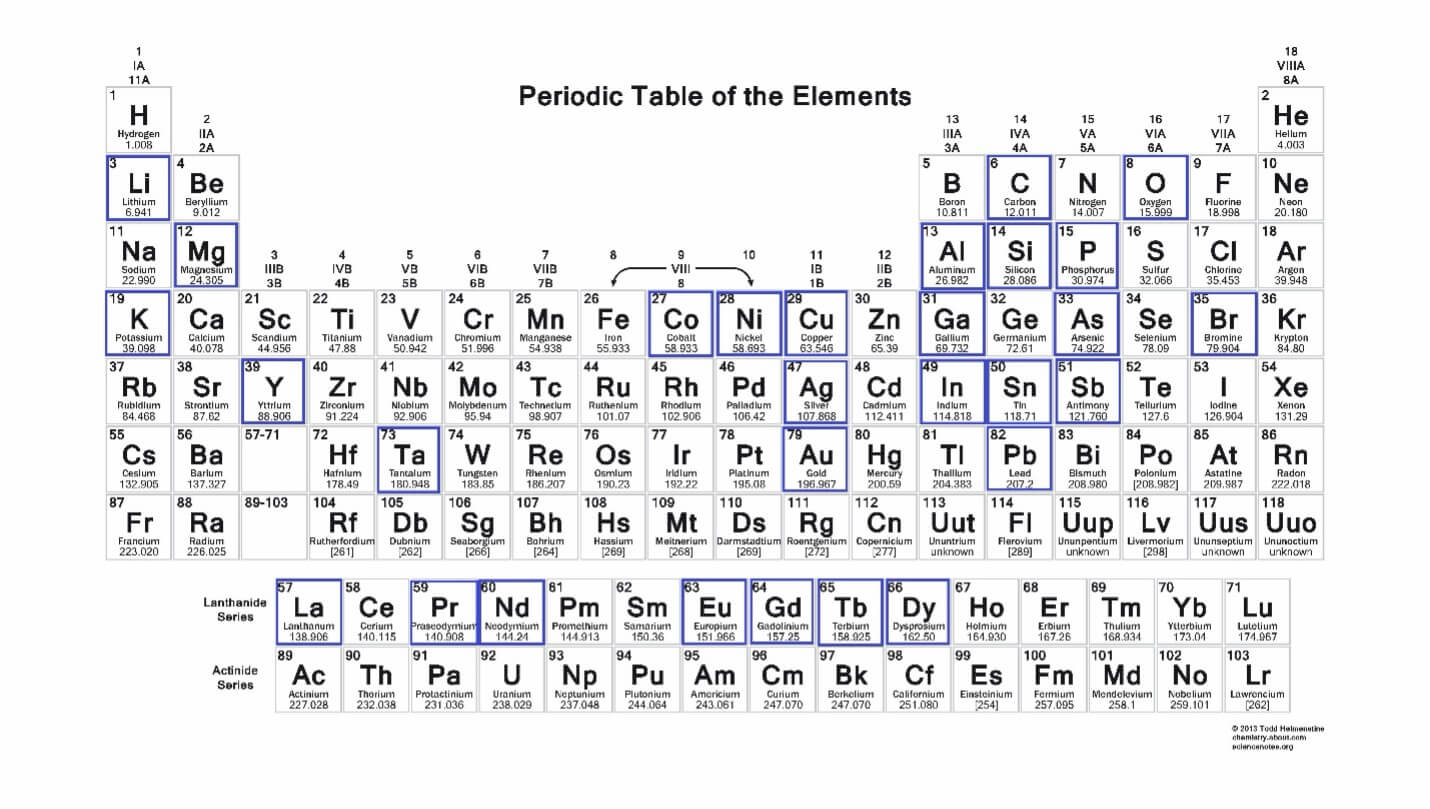

Electronic devices contain up to two dozen different metals. The list includes:

- Common, abundant metals (copper, aluminum, tin)

- Precious metals (gold, silver, platinum)

- Rare earth metals (neodymium, terbium, dysprosium)

The traditional source of these metals is mining. Mining ores from the earth and processing them is energy intensive and creates tons of toxic waste. It contributes to environmental destruction and human health hazards that are not acceptable if we want society to thrive in the coming years and decades.

One solution is urban mining, where metals are recovered from discarded electronics and put back into circulation. Plastics can be recovered and recycled as well, though metals offer much greater financial return.

E-waste processing typically focuses on extracting gold, which is in high demand because of the value per ounce. But there is good reason to recover all the metals inside electronics. Doing so avoids the damage caused by mining. It also reduces the risk of shortages of some of the rare earth metals needed to make specific components.

In 2017, Apple Computer voiced a BHAG—a big, hairy audacious goal—with its intention to make iPhones and other devices using no mined metals. It was an unusual step for the normally secretive company. But they put no deadline on the goal.

There has been progress. Apple is using recycled aluminum in product casings. The company has active research projects to increase its use of recycled content for over a dozen different materials, most of which are metals. This progress is encouraging, but our industry can do more.

If Apple had committed to a deadline for using only recycled metals, they might have made it happen by now. The technology exists to extract dozens of different metals from used electronic devices. The problem is that it doesn’t exist at scale. Without a big industry player like Apple supporting the necessary scaling, the capital investment to make it happen is not likely to appear.

For urban mining to increase, we need to overcome gaps in processing capabilities. Recycling facilities must have a ready supply of devices to process and an end market for all the recycled metals. If both of these are ensured, the facilities can pursue funding.

Public campaigns can help increase the supply of devices. The 2020 Olympics—although they didn’t happen until 2021—are a great example. Japan asked residents to deposit smartphones into specially marked kiosks so that recyclers could extract the gold, silver, and copper needed to make medals for the Olympic athletes. The incredibly successful campaign in 2017 and 2018 collected over 5 million phones, far more than they needed.

Even without a special event like the Olympics, electronics manufacturers can step up their take-back programs to encourage customers to return their old devices when they buy a replacement. Credit toward a new purchase would give more people a reason to trade in their used electronics.

Progress is happening, especially in Europe. Closing the Loop, based in The Netherlands, has a program to make electronics “waste neutral.” The process is similar to buying carbon credits.

When companies buy phones for their employees or dispose of old phones, they pay a small fee per device. Closing the Loop uses the funds to collect electronics in African countries where people do not have easy access to e-waste recycling. The collection process ensures they get responsibly recycled, locally if possible.

Increasing e-waste recycling rates is not the only avenue to pursue.

Right to Repair

Like many sustainability issues, the e-waste problem can be alleviated by starting at the design phase. A new regulation in the European Union (EU) went into effect earlier this year. The law strengthens consumers’ rights to repair their electronic devices. It is an offshoot of the EU’s 2009 Ecodesign Directive.

Like many environmental initiatives, the right to repair movement started in the EU but affects companies worldwide. OEMs will not produce a repairable version of their product for the EU market and a less repairable one for sale in the US.

Designers are being forced to consider repairability up front and must make replacement parts available to the market. Although the law doesn’t apply to phones or laptops—it only covers washing machines, dishwashers, refrigerators, monitors, and televisions—future regulations are in the works for those products.

Changes are coming, and OEMs realize they need to make their products more repairable. Apple and Samsung are making progress, although a bit more slowly than many wish. The MacBook Pro, for example, has a replaceable battery.

Customers in the EU already have an alternative for their smartphone purchases—Fairphone. The Fairphone is designed to be modular and repairable. The most recent model contains recycled content and conflict-free metals and comes with a 5-year warranty. These phones are only available in Europe, though. Those of us in North America will have to wait.

The Role of the Semiconductor Industry

If your company’s products are part of the electronics manufacturing supply chain, the e-waste problem is something you ought to consider. You can be part of the problem or part of the solution.

Here are some ways to help mitigate e-waste:

- If you buy metals, choose recycled content when possible

- Recover waste from your manufacturing process and find a market for it

- Ensure that used computers from your workplace get responsibly recycled

There are opportunities for companies that can offer solutions to improve:

- E-waste collection and distribution

- Design for repairability

- E-waste processing to extract as many materials as possible

What are you doing to make electronics more circular?